Take the Test? Skip the Test? Annual Seminar Offers Insights

Questions abound when it comes to tests and treatments.

- Is it better to take statins in hopes of averting heart disease or skip them to avoid the side effects?

- Is it better to get a test that might diagnose cancer so it can be treated? Or should one worry about a questionable diagnosis that would lead to treatment with significant side effects?

- Doctors may say it’s best to gain information from a test, but is it really necessary? Is it for the patient’s benefit or the benefit of someone else’s bottom line?

How do we know when a test or treatment will protect our health and when it might make things worse?

Annual Seminar Offers Another Approach

One approach creates a scenario where you can “see” how many people a test helps compared to how many experience side effects or other issues. That’s what Dr. Erik Rifkin and Dr. Andrew Lazris aim to do with their “Benefit/Risk Characterization Theater” approach.

Rifkin and Lazris will present a variety of healthcare situations in a “theater” scenario at The Alliance Annual Seminar on May 16.

This year, for the first time, The Alliance Annual Seminar is open to all C-suite and Human Resources benefit leaders. Learn more about events by The Alliance.

In a benefit-and-risk theater scenario, the audience is guided to visualize the impact of a test or treatment on a theater filled with 1,000 people. This information can then be used in shared decision-making, where the doctor and patient discuss risks and benefits and share in decisions about care.

When Shared Decision Making Is Lacking

In Rifkin and Lazris’ book, “Interpreting Health Benefits and Risks,” Rifkin tells the story of a decision-making dilemma that impacted his family in the 1990s. His 81-year-old father had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test during his annual physical and learned the levels were high, leading to a recommendation for a potentially painful biopsy of his prostate gland.

His doctor told him the test was absolutely necessary. Rifkin disagreed for multiple reasons, the most important being that his father had terminal emphysema with a life expectancy of two years at the most.

Yet Rifkin’s father would only agree to skip the biopsy if his doctor said it was alright to do so (Rifkin has a Ph.D. but is not a medical doctor).

Rifkin was able to speak with the doctor and persuade him to call his father and tell him the test was unnecessary. While he was pleased with the outcome, Rifkin notes that he “did not say what was really on my mind.”

For Rifkin, these were the real questions:

“Given his condition, I would like to have asked this doctor why it was necessary to determine levels of PSA in my father’s blood in the first place. Why did a conversation not occur about the course of treatment before the needle punctured my dad’s arm? Why didn’t the doctor attempt to address what was obviously a high level of uncertainty and apprehension?”

And perhaps most important, “Why wasn’t there any shared decision-making?”

Decision Aids

The Benefit/Risk Characterization Theater approach used by Rifkin and Lazris is considered a “decision aid” for shared decision-making. Decision aids help doctors and patients talk about the outcome of a decision in the short term and long term.

Lazris provided an example of how the Benefit/Risk Characterization Theater works as a decision aid in a National Public Radio article on “Why Some Doctors Hesitate to Screen Smokers for Lung Cancer.” . External Link. Opens in new window.Rifkin and Lazris also wrote an opinion article for the Baltimore Sun about the screening’s risks and benefits.

Lazris is a primary care physician in Columbia, Md. When considering whether to order a spiral Computerized Tomography (CT) scan to look for lung cancer in older patients who are current or former smokers, Lazris considers these facts:

- Not many people will benefit.

- A lot of people will get false alarms.

- A lot of people will get “excessive testing and potential harm.”

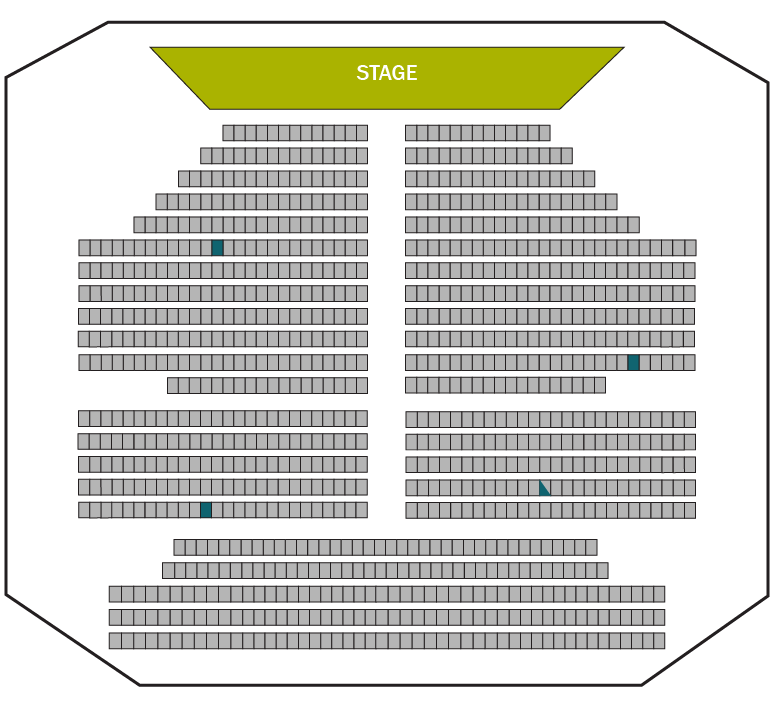

That’s where the theater image comes into play. This image shows how many deaths are averted when 1,000 people have an annual spiral CT scan to check for lung cancer.

Blue squares indicate the number of deaths averted.

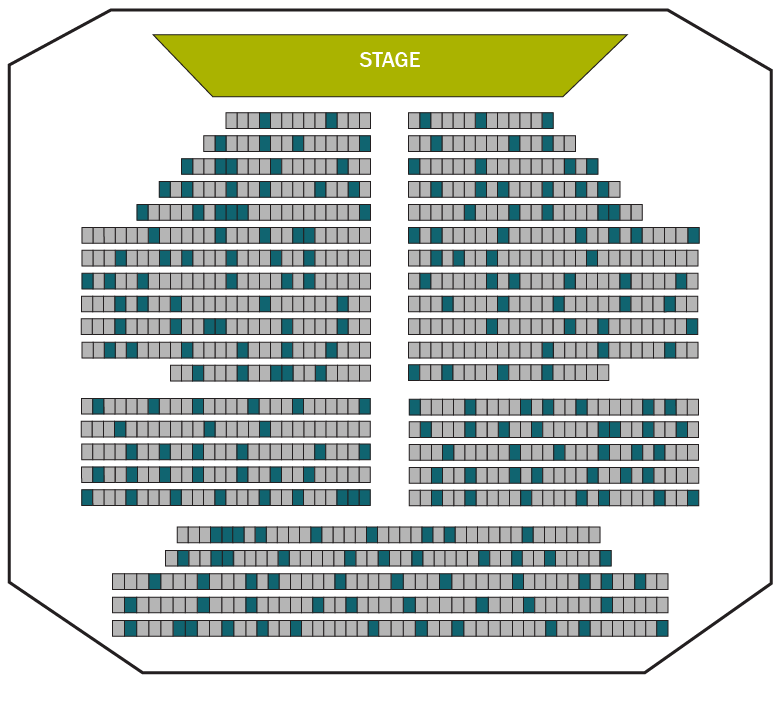

The next image shows how many people will get a “persistent” false positive result. Or a test result that, when repeated, indicates they have lung cancer even when they do not. As a result, they will have more tests, which means more exposure to radiation and more risk of complications. Plus, the stress of worrying about whether they have cancer.

Blue squares indicate the number of patients who will get a false positive.

Tests abound

The benefits of shared decision-making – and decision aids like the “risk theater” – multiply when you consider the number of different tests that patients may be asked to have.

Lazris and Rifkin emphasize that with every test, the goal is never to make the decision for the patient. Instead, as Lazris said in the NPR article, the goal is to help “patients understand the odds and then let them make the choice.”

[box]

Learn more:

- Oral Health and Chronic Condition – Cost Management with Dental Benefits

- How to Save Your Employees 50% on Primary Care Costs

[/box]